Censored by Linkedin

2nd June 2014: My friend Guo Jian was detained last night in China. 4 June Anniversary sadness ow.ly/xvVJL #TiananmenSquare

Find the full article above here:

Following writing the tweet/FB update/Linkedin update above I was written to by Linkedin. They advised that my followers on Linkedin would not be able to see my updates. I responded:

Four journalists spoke to me about the story following my update above, Fergus Ryan at China Spectator, Tania Branigan at The Guardian, Austin Ramsey at The New York Times and Gwynn Guilford at Quartz.

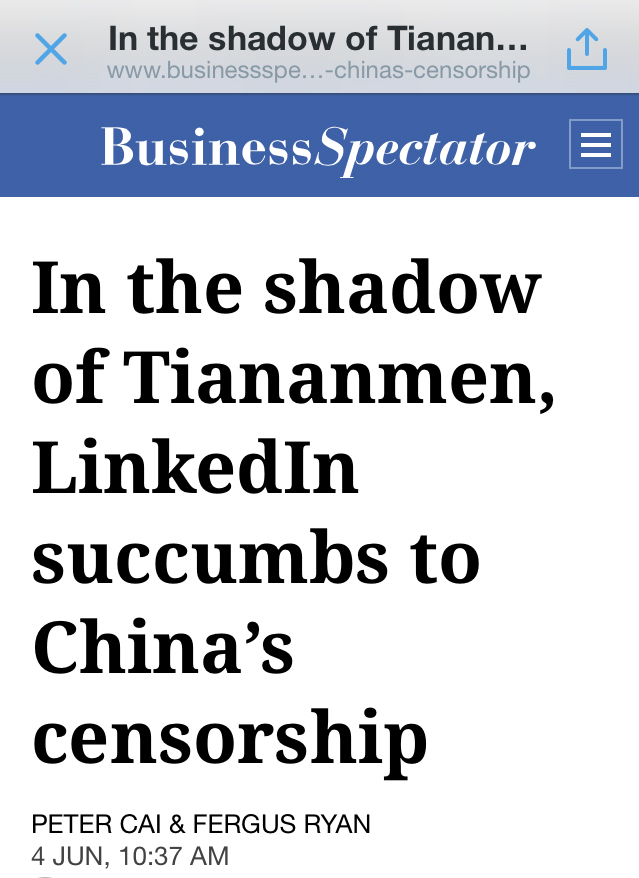

“I’m very unhappy about it. I think it’s really unprofessional. Especially as I was only sharing things that are already in the public domain,” Ms Couchman told China Spectator.

Find the full article here:

LinkedIn said: ‘To create value for our members … we will need to implement the Chinese government’s restrictions on content.’

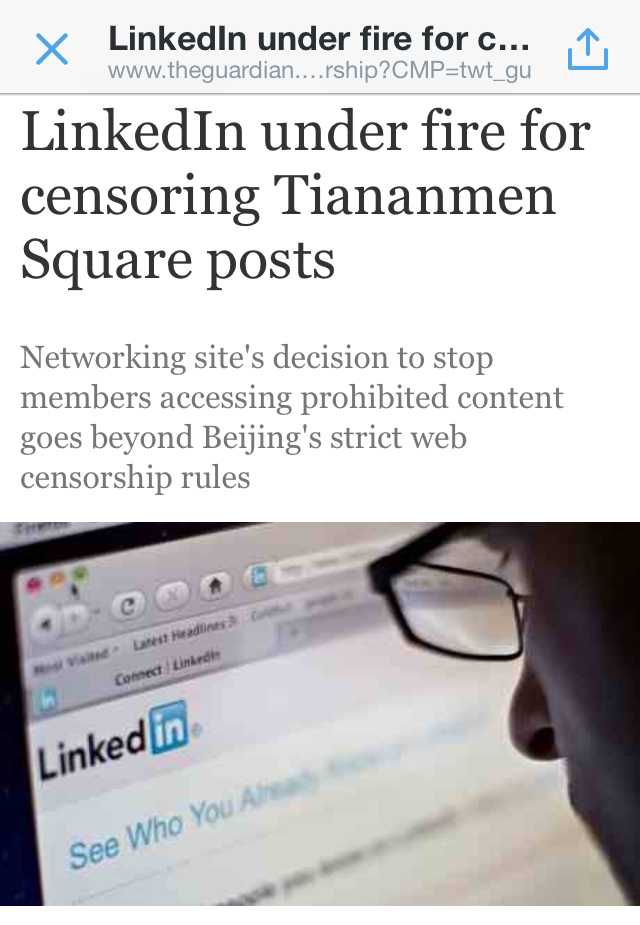

LinkedIn under fire for censoring Tiananmen Square posts

Networking site’s decision to stop members accessing prohibited content goes beyond Beijing’s strict web censorship rules

Tania Branigan in Beijing

The Guardian

Business networking site LinkedIn has said it will stop users seeing content posted from China that breaches the country’s strict censorship laws, after members complained that posts related to the Tiananmen anniversary had been blanked out.

LinkedIn is one of the few foreign social media services accessible from mainland China – where Facebook, YouTube, Twitter and others are blocked – and launched a Chinese-language service earlier this year, but does not have servers on the mainland.

Its decision goes beyond Beijing’s requirements to restrict what users in China see and effectively exports some Chinese controls on content, though a spokesman said it was intended to protect users.

Artist Helen Couchman and journalist Fergus Ryan both reported receiving messages warning them that items they had posted would not be seen by LinkedIn members as they “contained content prohibited in China”.

Couchman, who lived in China for several years, said the decision to block articles she had shared about detained artist Guo Jian was outrageous. “I wasn’t even sharing an opinion,” she added.

Guo, who has Australian citizenship, was taken away by police in Beijing shortly after the publication of an interview in which he described participating in 1989’s pro-democracy protests in Tiananmen Square and discussed a work he had created commemorating the bloody crackdown.

Ryan said in an article for the China Spectator site, for which he reports from China, that he too had posted pieces about Guo.

Roger Pua, director of corporate communications in the Asia-Pacific region for LinkedIn, said the company strongly supported freedom of expression, but added: “To create value for our members in China and around the world, we will need to implement the Chinese government’s restrictions on content, when and to the extent required … Members in China will not be able to access content that is prohibited in China.”

But the site is also preventing people outside China from seeing material that censors disapprove of if it was first posted from China.

Pua said: “Outside of China, members will be able to view content that is restricted in China, unless that content originated in China – this is to protect the privacy and security of the member who posted that content.

“ “LinkedIn, by its nature, is a professional network and not prone to conversations that are political in nature. We think the impact is very, very small.”

While most Chinese rely on heavily censored Chinese services – such as the Sina Weibo microblog – some, including many activists and dissidents, use VPNs or other methods to post material on Twitter and Facebook.

LinkedIn said in February that it was applying to set up operations in China, acknowledging it would need to comply with Chinese government demands to filter content.

Cynthia Wong, senior internet researcher at Human Rights Watch, said that while she was not aware of the LinkedIn case, “the best practice that has emerged is that companies will not censor for the world”.

She added: “If there’s material that needs to be taken down in one jurisdiction, competitors will leave it up for the rest of the world – precisely for the reason that we should not allow the internet to go to the lowest common denominator; it should not be scrubbed of everything bar material acceptable to the least tolerant government out there.”

Michael Anti, a Chinese commentator, said: “It means Linkedin now publicly accepts Chinese censorship rule for anyone who is in mainland China, without any hesitation.”

He compared it to Microsoft’s decision to remove his Chinese-language blog in 2005 – a move that sparked international criticism.

In that case, he said, “the company felt wrong and shameful. So you know how much internet freedom we have lost worldwide in the past decade.”

LinkedIn is censoring posts about Tiananmen Square by Gwynn Guilford

4th June 2014

Find the full article here:

http://qz.com/216691/linkedin-is-censoring-posts-about-tiananmen-square-even-outside-mainland-china

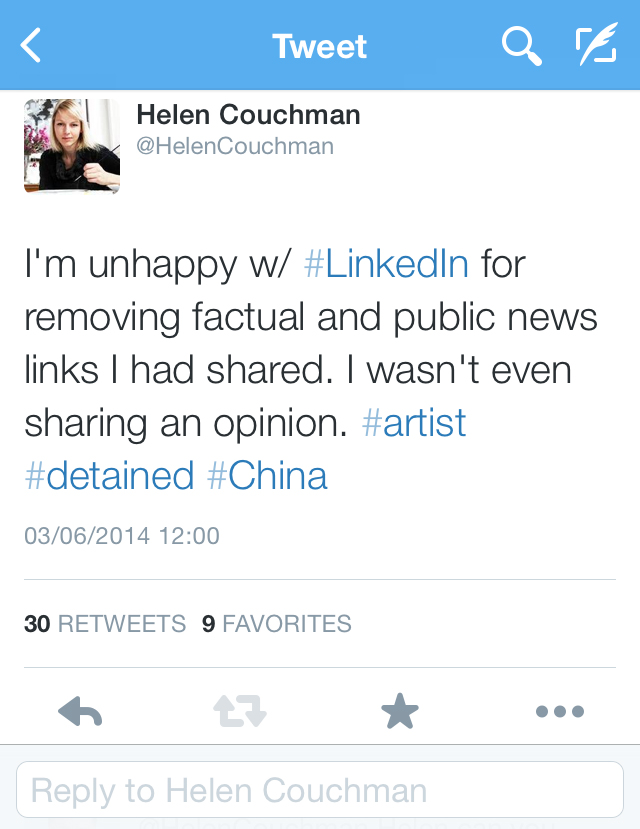

…Another person to encounter LinkedIn’s censorship was Helen Couchman, an artist and longtime Beijing resident who moved to Britain in February 2013, according to the China Spectator. Couchman said that LinkedIn deleted her post linking to an article about the Chinese authorities’ detention of Guo Jian, a Chinese-Australian artist and friend of Couchman’s. (She shared the same article on Facebook and Twitter, where her posts are still available.) She subsequently tweeted her dismay at LinkedIn…

Couchman’s LinkedIn account appears to be hosted on the mainland China site, cn.linkedin.com, which might explain why her posts fell under its censorship…