Beijing Excavations: An Interview with Helen Couchman – Whitehot Magazine

Beijing Excavations: An Interview with Helen Couchman

whitehot | August 2011

by Travis Jeppesen

The hutongs – or traditional lanes – of the Xicheng area surrounding Houhai Lake in downtown Beijing present a picture of a rapidly disappearing facet of city life. Filled with hidden courtyards and single-story houses, often dating back hundreds of years, walking among them reminds one of what Beijing used to be like, prior to the rapid modernization that has taken place in the last ten years, which has seen the erection of countless skyscrapers, high rise apartment buildings, and soulless American-style shopping centers.

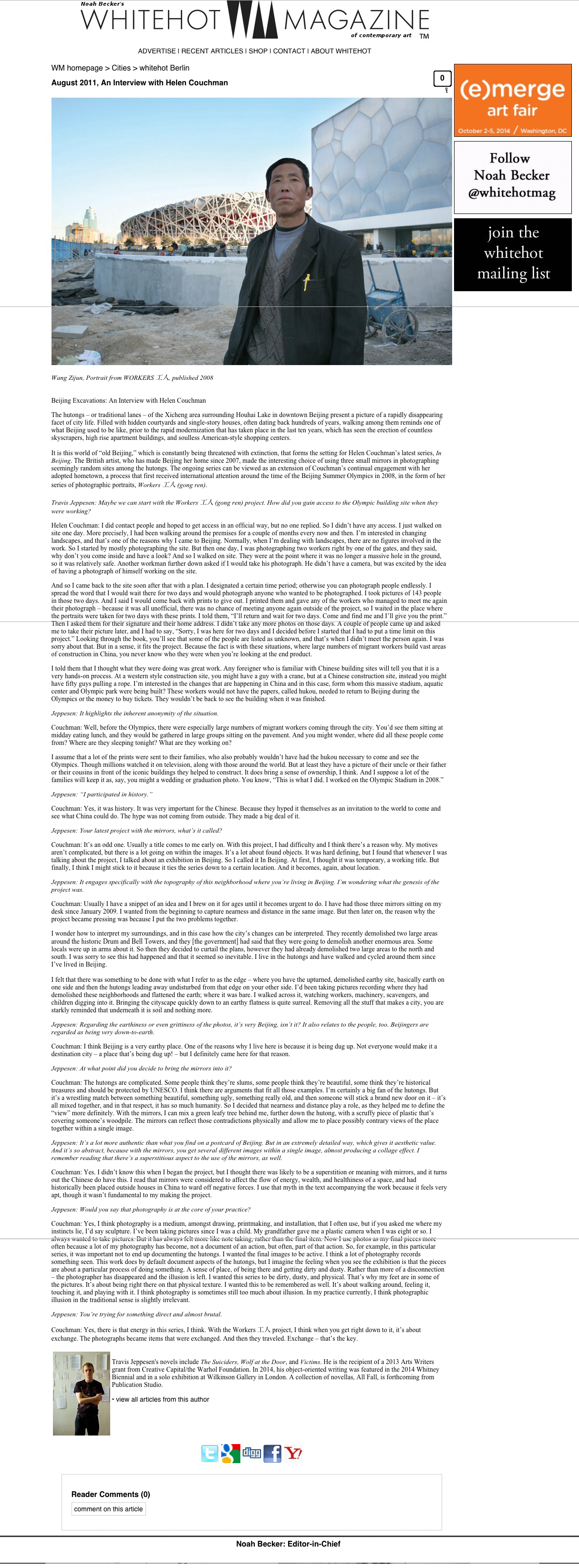

It is this world of “old Beijing,” which is constantly being threatened with extinction, that forms the setting for Helen Couchman’s latest series, In Beijing. The British artist, who has made Beijing her home since 2007, made the interesting choice of using three small mirrors in photographing seemingly random sites among the hutongs. The ongoing series can be viewed as an extension of Couchman’s continual engagement with her adopted hometown, a process that first received international attention around the time of the Beijing Summer Olympics in 2008, in the form of her series of photographic portraits, Workers 工人 (gong ren).

Travis Jeppesen: Maybe we can start with the Workers 工人 (gong ren) project. How did you gain access to the Olympic building site when they were working?

Helen Couchman: I did contact people and hoped to get access in an official way, but no one replied. So I didn’t have any access. I just walked on site one day. More precisely, I had been walking around the premises for a couple of months every now and then. I’m interested in changing landscapes, and that’s one of the reasons why I came to Beijing. Normally, when I’m dealing with landscapes, there are no figures involved in the work. So I started by mostly photographing the site. But then one day, I was photographing two workers right by one of the gates, and they said, why don’t you come inside and have a look? And so I walked on site. They were at the point where it was no longer a massive hole in the ground, so it was relatively safe. Another workman further down asked if I would take his photograph. He didn’t have a camera, but was excited by the idea of having a photograph of himself working on the site.

And so I came back to the site soon after that with a plan. I designated a certain time period; otherwise you can photograph people endlessly. I spread the word that I would wait there for two days and would photograph anyone who wanted to be photographed. I took pictures of 143 people in those two days. And I said I would come back with prints to give out. I printed them and gave any of the workers who managed to meet me again their photograph – because it was all unofficial, there was no chance of meeting anyone again outside of the project, so I waited in the place where the portraits were taken for two days with these prints. I told them, “I’ll return and wait for two days. Come and find me and I’ll give you the print.” Then I asked them for their signature and their home address. I didn’t take any more photos on those days. A couple of people came up and asked me to take their picture later, and I had to say, “Sorry, I was here for two days and I decided before I started that I had to put a time limit on this project.” Looking through the book, you’ll see that some of the people are listed as unknown, and that’s when I didn’t meet the person again. I was sorry about that. But in a sense, it fits the project. Because the fact is with these situations, where large numbers of migrant workers build vast areas of construction in China, you never know who they were when you’re looking at the end product.

I told them that I thought what they were doing was great work. Any foreigner who is familiar with Chinese building sites will tell you that it is a very hands-on process. At a western style construction site, you might have a guy with a crane, but at a Chinese construction site, instead you might have fifty guys pulling a rope. I’m interested in the changes that are happening in China and in this case, form whom this massive stadium, aquatic center and Olympic park were being built? These workers would not have the papers, called hukou, needed to return to Beijing during the Olympics or the money to buy tickets. They wouldn’t be back to see the building when it was finished.

Jeppesen: It highlights the inherent anonymity of the situation.

Couchman: Well, before the Olympics, there were especially large numbers of migrant workers coming through the city. You’d see them sitting at midday eating lunch, and they would be gathered in large groups sitting on the pavement. And you might wonder, where did all these people come from? Where are they sleeping tonight? What are they working on?

I assume that a lot of the prints were sent to their families, who also probably wouldn’t have had the hukou necessary to come and see the Olympics. Though millions watched it on television, along with those around the world. But at least they have a picture of their uncle or their father or their cousins in front of the iconic buildings they helped to construct. It does bring a sense of ownership, I think. And I suppose a lot of the families will keep it as, say, you might a wedding or graduation photo. You know, “This is what I did. I worked on the Olympic Stadium in 2008.”

Jeppesen: “I participated in history.”

Couchman: Yes, it was history. It was very important for the Chinese. Because they hyped it themselves as an invitation to the world to come and see what China could do. The hype was not coming from outside. They made a big deal of it.

Jeppesen: Your latest project with the mirrors, what’s it called?

Couchman: It’s an odd one. Usually a title comes to me early on. With this project, I had difficulty and I think there’s a reason why. My motives aren’t complicated, but there is a lot going on within the images. It’s a lot about found objects. It was hard defining, but I found that whenever I was talking about the project, I talked about an exhibition in Beijing. So I called it In Beijing. At first, I thought it was temporary, a working title. But finally, I think I might stick to it because it ties the series down to a certain location. And it becomes, again, about location.

Jeppesen: It engages specifically with the topography of this neighborhood where you’re living in Beijing. I’m wondering what the genesis of the project was.

Couchman: Usually I have a snippet of an idea and I brew on it for ages until it becomes urgent to do. I have had those three mirrors sitting on my desk since January 2009. I wanted from the beginning to capture nearness and distance in the same image. But then later on, the reason why the project became pressing was because I put the two problems together.

I wonder how to interpret my surroundings, and in this case how the city’s changes can be interpreted. They recently demolished two large areas around the historic Drum and Bell Towers, and they [the government] had said that they were going to demolish another enormous area. Some locals were up in arms about it. So then they decided to curtail the plans, however they had already demolished two large areas to the north and south. I was sorry to see this had happened and that it seemed so inevitable. I live in the hutongs and have walked and cycled around them since I’ve lived in Beijing.

I felt that there was something to be done with what I refer to as the edge – where you have the upturned, demolished earthy site, basically earth on one side and then the hutongs leading away undisturbed from that edge on your other side. I’d been taking pictures recording where they had demolished these neighborhoods and flattened the earth; where it was bare. I walked across it, watching workers, machinery, scavengers, and children digging into it. Bringing the cityscape quickly down to an earthy flatness is quite surreal. Removing all the stuff that makes a city, you are starkly reminded that underneath it is soil and nothing more.

Jeppesen: Regarding the earthiness or even grittiness of the photos, it’s very Beijing, isn’t it? It also relates to the people, too. Beijingers are regarded as being very down-to-earth.

Couchman: I think Beijing is a very earthy place. One of the reasons why I live here is because it is being dug up. Not everyone would make it a destination city – a place that’s being dug up! – but I definitely came here for that reason.

Jeppesen: At what point did you decide to bring the mirrors into it?

Couchman: The hutongs are complicated. Some people think they’re slums, some people think they’re beautiful, some think they’re historical treasures and should be protected by UNESCO. I think there are arguments that fit all those examples. I’m certainly a big fan of the hutongs. But it’s a wrestling match between something beautiful, something ugly, something really old, and then someone will stick a brand new door on it – it’s all mixed together, and in that respect, it has so much humanity. So I decided that nearness and distance play a role, as they helped me to define the “view” more definitely. With the mirrors, I can mix a green leafy tree behind me, further down the hutong, with a scruffy piece of plastic that’s covering someone’s woodpile. The mirrors can reflect those contradictions physically and allow me to place possibly contrary views of the place together within a single image.

Jeppesen: It’s a lot more authentic than what you find on a postcard of Beijing. But in an extremely detailed way, which gives it aesthetic value. And it’s so abstract, because with the mirrors, you get several different images within a single image, almost producing a collage effect. I remember reading that there’s a superstitious aspect to the use of the mirrors, as well.

Couchman: Yes. I didn’t know this when I began the project, but I thought there was likely to be a superstition or meaning with mirrors, and it turns out the Chinese do have this. I read that mirrors were considered to affect the flow of energy, wealth, and healthiness of a space, and had historically been placed outside houses in China to ward off negative forces. I use that myth in the text accompanying the work because it feels very apt, though it wasn’t fundamental to my making the project.

Jeppesen: Would you say that photography is at the core of your practice?

Couchman: Yes, I think photography is a medium, amongst drawing, printmaking, and installation, that I often use, but if you asked me where my instincts lie, I’d say sculpture. I’ve been taking pictures since I was a child. My grandfather gave me a plastic camera when I was eight or so. I always wanted to take pictures. But it has always felt more like note taking, rather than the final item. Now I use photos as my final pieces more often because a lot of my photography has become, not a document of an action, but often, part of that action. So, for example, in this particular series, it was important not to end up documenting the hutongs. I wanted the final images to be active. I think a lot of photography records something seen. This work does by default document aspects of the hutongs, but I imagine the feeling when you see the exhibition is that the pieces are about a particular process of doing something. A sense of place, of being there and getting dirty and dusty. Rather than more of a disconnection – the photographer has disappeared and the illusion is left. I wanted this series to be dirty, dusty, and physical. That’s why my feet are in some of the pictures. It’s about being right there on that physical texture. I wanted this to be remembered as well. It’s about walking around, feeling it, touching it, and playing with it. I think photography is sometimes still too much about illusion. In my practice currently, I think photographic illusion in the traditional sense is slightly irrelevant.

Jeppesen: You’re trying for something direct and almost brutal.

Couchman: Yes, there is that energy in this series, I think. With the Workers 工人 project, I think when you get right down to it, it’s about exchange. The photographs became items that were exchanged. And then they traveled. Exchange – that’s the key.

* * *

Travis Jeppesen is the author of five books, including Victims, the novel chosen by Dennis Cooper to debut his “Little House on the Bowery” imprint for Akashic Books, and Disorientations: Art on the Margins of the “Contemporary”. His most recent book is Dicklung & Others, a collection of poetry. He lives in Berlin.

• view all articles from this author

Beijing Excavations: An Interview with Helen Couchman – Whitehot Magazine